“The Heavens Above and the Earth Below”: A Study of Cosmology in the Biblical and Rabbinic Sources

Overview: How the ancient Israelites and, later, rabbinic Jews saw the Earth, the Cosmos, and astronomy. Did they believe in a flat Earth like the rest of society? What were the sky’s limits and in the depths below land? The answers are fascinating and might surprise you!

My conversation with an ancient Israelite

I was airdropped into 7th-century BCE Israel and met a nice Jewish farmer near the village granary at a Shechem suburb. I was surprised by his intimate knowledge of Earth and nature. The fascinating conversation was interrupted by a sudden thunderstorm that sent us dashing under the closest grove tree. He commented on the thunder, calling it “God’s roar.” After I asked for clarification, he noted the ancient theological belief that thunder resulted from God roaring in the heavens. With keen interest I passed him a branch, and he began drawing on the soft earth.

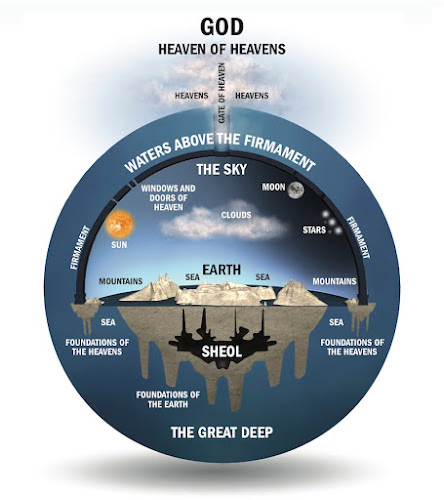

A disk surrounded by a wider disk, and encircled by a great firmament. What’s a firmament? I vaguely remembered it from Yeshiva when we hastily studied the complex biblical verses and talmudic passages on the subject. Luckily Utz was there to explain it to me – but first I needed to leave my 21st-century Copernican perspective of a sphere-shaped Earth.

Flat Earth in Tanakh and Talmud

We often take our knowledge of the sphere-shaped Earth for granted. But for the vast majority of our history, all humans believed in a flat Earth – just as we see it with our own eyes. Did the ancient Israelites have the same erroneous belief like the rest of society at the time, or perhaps were they enlightened with the knowledge we now know of a sphere-shaped Earth? All evidence suggests the Israelites believed what the Egyptians, Assyrians, and Babylonians all believed to be true – that the Earth was flat. In fact, the Jewish holy books, both biblical and rabbinic – take a flat Earth for granted, as we shall demonstrate.

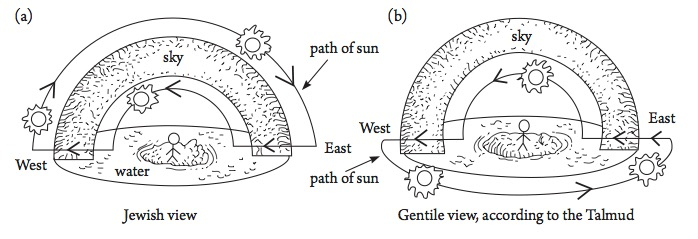

The most obvious example of the talmudic sages’ perception of a flat Earth appears in a dialogue about the Sun’s path at night.1 The sages of Israel had an astronomical disagreement with the sages of the world. The Israelite sages believed that the Sun passes through the firmament (“rakia”) from East to West and reverses course at night behind (or above) the firmament to return back to the East for sunrise. The non-Jewish sages,2 however, believed that the Sun continues its course after sunset and finishes a rotation under Earth. On this debate, Rebbi comments that it appears that the non-Jewish sages are correct, since at night the waters feel hotter than the atmosphere around it (implying that the Sun heats the waters from beneath at night).3

From Judah Landa. Torah and Science. Ktav 1991. p.63.

Rebbi’s perception that the Sun heats the waters overnight from below, implies a flat Earth whose waters can be heated from below. Moreover, the sages of Israel’s perception of a nightime in which the Sun leaves the firmament implies a lack of knowledge that there is always a day and night somewhere around the round globe.4

This idea is expressed in our prayer book (Siddur) today:

[God] who opens daily the eastern gate and pierces the windows of the firmament, taking the Sun out of its place and the Moon out of its resting area.

- Siddur, Shabbat morning prayers

The prayer is based on the primitive cosmological belief of a flat Earth with a set time for sunrise. It also takes for granted the idea of a firmament breached by windows for the Sun to pass through as sunrise, as the Talmud suggests.5

Another indication of the rabbinic belief in a flat Earth is the statement of Rabbi Nathan in Pesachim 94a. He says that the whole Earth sits under one star. The proof, he argues, is that if one looks at the positioning of this one star, and then walks to the other end of the world – that same star will still be in the same position in the sky. In the spherical model of Earth, this wouldn’t be possible, as the star would actually disappear from view at one point. This is aside from the general misunderstanding of Rabbi Nathan regarding the distance of the stars. He clearly imagines a much closer star than in reality. In reality, the great distance of the stars from Earth wouldn’t make any repositioning of it in the sky noticeable to the human eye. Moreover, in the spherical model of Earth, every single star can be regarded as hovering over Earth; it would just depend on where on the globe you are standing.

A flat Earth was the established “science” of its day, with a spherical Earth only being thought up in Greece in the 6th-century BCE and popularly accepted only centuries later. There are no indications anywhere in ancient Jewish literature that indicate they had an understanding of the spherical Earth before the rest of the world did.

In fact, it is clear that the authors of the various biblical books of Tanakh had a primitive comprehension of the cosmological sciences and believed in a flat Earth. Daniel 4:8 describes a tree growing so high that it can be seen at the very ends of Earth – an impossibility in the spherical model of Earth. If a tree were to grow ever so high in America, that tree could not be seen in Australia which is on the other side of the spherical globe.

Psalm Ch. 19 poetically describes the Sun going quiet at night and rejoicing in the morning at sunrise. This perceives an absolute sunrise and sunset – which does not happen in the spherical model of an ever-rotating Sun. We now know that each region in the world has its own time of sunrise and sunset. Similarly, the psalmist suggests that the Sun’s rays can be seen all across the Earth during daytime – again, misunderstanding the nature of the Sun’s orbit around the spherical globe.

His rising-place is at one end of heaven,

and his circuit reaches the other;

nothing escapes his heat.

- Psalm 19:7

The early rabbinic literature does feature one possible reference to a spherical Earth,6 though it may just be a belief in a rounded Earth submerged in water.7 Moreover, it was an opinion of an individual rabbi taking it from Greek sources concerning a legend of Alexander the Great riding the sky via an eagle and seeing a round/spherical Earth from above. Later rabbinic texts, starting from the 12th-century make clearer references to a spherical Earth, as the science of a spherical Earth advanced throughout the world.8 The model of a (slightly) rounded Earth submerged in water is highlighted by biblical and rabbinic texts that speak of Israel, and Jerusalem in particular, as being at the “top”9 and “center”10 of the world.

The Rakia (“firmament”)

Hand-in-hand with the belief in a flat Earth was the ancient nearly-universal belief in a solid dome stretched across the skies. This dome had the Sun, Moon, and stars all pinned inside of it. The purpose of this dome was multifunctional – it held the celestial bodies in the skies – lest they fall on us. But perhaps its main function was to keep the vast ocean of heavenly waters from falling down.

Genesis 1 describes the creation of this firmament:

God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the water, that it may separate water from water.”

God made the firmament, and it separated the water which was below the firmament from the water which was above the firmament. And it was so.

- Verses 6-7

The water above is likely where the etymology of shamayim – the Hebrew for heavens – comes from: sham- mayim “there are the waters.” Psalm 148:4 states

Praise Him, highest heavens,

and you waters that are above the heavens.

This water was perhaps an explanation to the ancients of why the sky is blue. We now know that the sky is blue due to distance and the ocean is blue only because it reflects the skies above it. They also possibly saw it as the source of storm rains, like the Great Flood in Genesis 7:11, which describes “the storehouses of heaven” opening and rain pouring down.

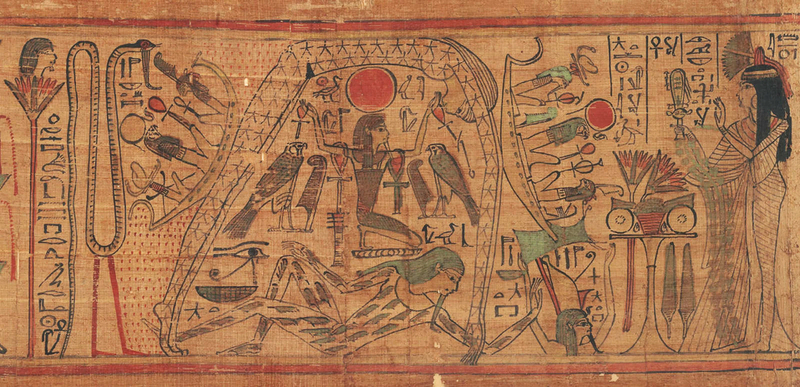

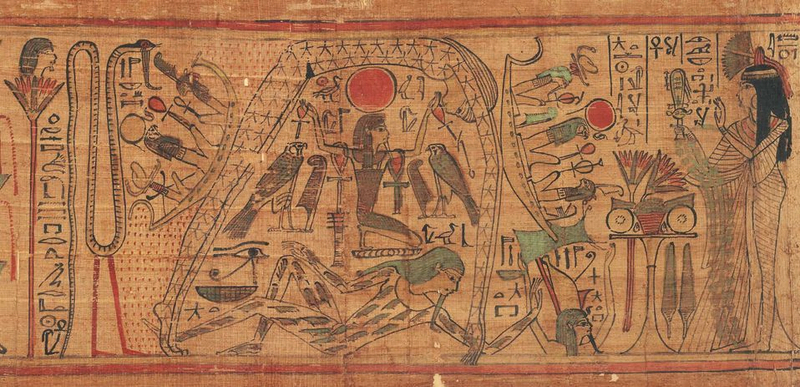

We know much of this perceived dome from the vast literature from the ancient Near Eastern cultures. The ancient Egyptian paintings in the temples11 depict the goddess Nut stretching her body like an arch over Earth with the Sun, Moon, and stars all spangled throughout her body. The paintings and its accompanying hieroglyphics make clear that the ancient Egyptians believed in a sky made of a solid entity.

In this picture painted in an ancient Egyptian papyrus,12 we can see goddess Nut arching over Earth. Above her body are the upper waters being travelled by boat. The significance of these boats will be explored later.

The Enuma Elish is a babylonian epic detailing the mythological beginnings when the great deities battled for supremacy and formed Earth. The Genesis 1 creation account is strikingly similar to this then-popular second-millenium BCE epic and was likely influenced by it. Tablet 4 of the epic describes the chief babylonian deity Marduk slaying his competitor Tia-Mat and splitting her body in two. He uses one half to form the upper waters and her skin is stretched out as to be the sky and prevent the waters from falling below.13 The ancient Celts all the way in Western Europe are said to have most feared the sky falling on their heads, according to ancient accounts.14 This is because they too imagined the sky as a firm entity containing the Sun, Moon, and stars.

Job 37:18 states:

Can you help him stretch out the heavens,

Firm as a mirror of cast metal?

The Talmud also continues with this popular notion of the solid-dome sky. According to one sage, the sky is made up of seven layers, or levels, each serving a different function.15 According to another, its solid component is just a fingerbreadth in width (like a metal vault holding water16),17 while according to another it’s a 50-year’s journey deep.18

The sages state that the distance from Earth to the sky is less than the distance from East to West.19 Evidently, it understands the “sky” (rakia) to be a specific (solid) entity rather than just the “air” that we now think of when we say sky. Similarly, Genesis 11:4 describes the intention of the Sumerians to build a tower whose tip “reaches the sky.” While this can be understood to be just an expression, recognizing that the ancients believed in an actual space in which the firmament-sky began helps give context to this phrase. They intended to build a tower that reached the firmament-sky.20

In one narrative, a talmudic sage does in fact touch the sky:

An Arab also said to me: Come, I will show you the place where the Earth and the heavens touch each other. I took my basket and placed it in a window of the heavens. After I finished praying, I searched for it but did not find it. I said to him: Are there thieves here? He said to me: This is the heavenly sphere that is turning around; wait here until tomorrow and you will find it again.

- Bava Batra 74a.

Evidently, this legend has the sage putting his basket into one of the “windows” of the firmament. These windows allow for the passage of the Sun, Moon, and stars during their daily rotation.21 They also allow for rainfall during floods and during plentiful rainfall seasons. Many biblical verses make mention of the “windows of heaven.”22 While the ancients did have an understanding of the rainclouds,23 they nevertheless seemed to also believe in an extra reserve of rain that came from the waters above. These reserves came with God’s blessing and the heavenly windows needed to be opened for the rain to fall down.24

Many varying cultures spoke of these heavenly windows, and most notably the non-canonized apocryphal book of Enoch (c. 2nd-century BCE) has this vivid depiction:

“I went to the extreme ends of the Earth and saw there huge beasts, each different from the other and different birds (also) differing from one another in appearance, beauty, and voice. And to the east of those beasts, I saw the ultimate ends of the Earth which rests on the heaven. And the gates of heaven were open, and I saw how the stars of heaven come out…”

- I Enoch 33:1-2.

The Jerusalem Talmud25 in the context of the firmament speaks of the “365 windows which God created for the world.” This is a reference to the 365 days of the year in which the Sun appears at a different spot on the horizon on each day of the year. This coincides with the rabbinic belief that the Sun leaves and enters the firmament each day at sunrise and sunset.26

There was also a belief that snow and hail were stored away in heavenly vaults or warehouses. Talmudic passages describe these vaults and Job makes reference to them as well.27 God is in charge of opening these at the proper times. The author of Psalm 104 believed that God’s gaze caused Earthquakes and his touch volcanoes.28 Although this can be perhaps a poetic, non-literal description.

Because of this flat-Earth perspective, the ancient Israelites and later rabbis believed in an unformed Northern sky. In the Northern Hemisphere of Earth, the Sun rises in the East, travels the South, and sets in the West. It’s never in the North because the Sun’s rotation is at the axis of Earth (the equator) which travels to the south of the Northern hemisphere. But the ancient Israelites had no understanding of a Southern Hemisphere in a sphere-shaped Earth. Therefore the Sun’s specifically southern route was somewhat puzzling.

According to one talmudic passage, the Sun never passes the North because it turns around above the firmament and circles back the other way above the firmament. Several biblical verses hint to the North skies being “unfinished,” perhaps a reference to the fact that the Sun and Moon never appear there.29

Bereshit Rabbah 4:2-5 contains the most vivid descriptions of the “rakia” (firmament) mentioned in Genesis 1. It is described as having “congealed” on the second day of creation,30 as being a separate entity than the lower part of the sky (what we might call “air”), and as being the vault for a large pool of water above it.

Based on everything cited above, it becomes evident that attempts to translate “rakia” as simply the “sky,” “air,” or “clouds” are fraught with error. Furthermore, attempts to explain these statements as all being figurative, poetic, and non-literal are driven by a bias of perceived infallibility on the part of these ancient authors, believed to be divinely-inspired. There are several issues with explaining all these statements concerning the firmament to be non-literal:

- There is a treasure-trove of ancient literature from around the world that suggests everyone had these cosmological viewpoints. It is very natural for the Israelites to have had the same viewpoints as everyone else on this.

- There are no references to a spherical-shaped Earth in Tanakh or the Talmud. This would be odd had they actually known the proper sciences of astronomy and cosmology but chose to keep it a secret from the world and from their writings.

- None of the context of these statements implies a figurative or nonliteral setting. Some of the statements are actually in a halachic discussion, implying an attempt to explain literal cosmology.

- There are no apparent deeper meanings to these statements. Is the deeper meanings perhaps a secret for the sages alone? Seems unlikely.

We have demonstrated that the authors of Tanakh and the Talmudic sages believed in a (1) flat Earth, (2) a solid-dome firmament above it, (3) a massive ocean of water above that. But the clues their literature leaves behind paints an even more fascinating viewpoint of the Earth they lived on and the heavens above their heads.

Earth’s Foundations

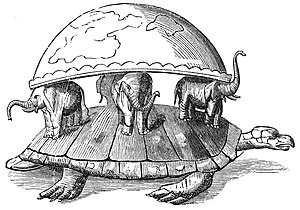

As any architect knows, every building must have proper foundations. Surely the Earth – a masterpiece of God’s creation – must have the most mighty foundations to keep it standing. Some ancient cultures, like the Hindu, Chinese, and some Native American cultures, believed that Earth lay atop titan elephants who themselves stood atop a behemoth turtle. The occasional Earthquake would only reinforce these perceptions.

The Israelites did not share this particular belief, but they did make frequent mention of some sort of pillars/foundations on which Earth stood.

“He established the Earth on its foundations,

so that it shall never totter.”

- Psalm 104:5

These foundations (perhaps rock-like) were covered by the great ocean.

“You made the deep cover it as a garment;

the waters stood above the mountains.”

- Ibid. v. 6

These foundations are mentioned throughout Tanakh in various contexts. Interestingly, the Talmud debates how many pillars there are for Earth with some saying twelve, others seven, and others one.31

Job 26:7 implies a belief that Earth is suspended over nothing. This may indicate a recognition that even the foundations aren’t enough to explain how Earth ultimately stands. Perhaps this is why the Talmud warns against the layman asking about “what is above” and “what is below.”32 Later on, the Talmud suggests that the foundations lie on a mighty wind, which lies on God’s hands.33

The concept of Earth’s foundations is a recurring theme in ancient Near Eastern cultures.

Sheol Netherworlds

Yet another fascinating feature of Israelite cosmology was rooted in another popular perception of the ancient Near East. Changing our gaze from on high to down below, we now look at the underworld brimming with the spirits of the dead, in a chamber known in biblical and canaanite mythology as “Sheol.”

The afterlife of Tanakh is vastly different from the one portrayed in later Talmudic sources. Talmudic ideas of the afterlife included a paradise and a hell – features likely influenced by the dominant Zoroasitic culture of the time. Similarly, the concept of a resurrection from the dead is also not featured in the biblical sources (until the late book of Daniel).34

In contrast, the biblical sources talk of an underground space dedicated to the dead, called Sheol, where both the righteous and wicked end up. With less than 100 mentions of Sheol throughout Tanakh, we know little of it but can piece together hints and clues. Additionally, the Canaanite sources can help us further understand the context in which Sheol was understood by the ancient Israelites.

Biblical figures, including the most righteous, talk of “joining their ancestors” upon death.35 For example,

Abraham breathed his last, dying at a good ripe age, old and contented; and he was gathered to his kin.

- Genesis 25:8

While many have erroneously interpreted this to be a reference to paradise, the reality is that it’s more likely referring to Sheol. This interpretation is supported by Ps. 49:20 and the surrounding context. Similarly, explaining it to be a reference to being buried in the burial lot of their ancestors is similarly flawed since Abraham – as well as many others by whom this phrase is used – was not buried at his ancestor’s plot.36

The Psalmists describe Sheol as a place in which the spirits do not have any recollection of God whatsoever.37

True to his character, Ecclesiastes (Kohelet) paints an even gloomier picture:

For the same fate is in store for all: for the righteous, and for the wicked; for the good and pure, and for the impure…

That is the sad thing about all that goes on under the Sun: that the same fate is in store for all…

For he who is reckoned among the living has something to look forward to—even a live dog is better than a dead lion—since the living know they will die. But the dead know nothing; they have no more recompense, for even the memory of them has died.

Their loves, their hates, their jealousies have long since perished; and they have no more share till the end of time in all that goes on under the Sun…

Whatever it is in your power to do, do with all your might. For there is no action, no reasoning, no learning, no wisdom in Sheol, where you are going.

- Ecclesiastes 9:2-10

These passages, among others, illustrate the early Israelite conception of an afterlife. Both the righteous and wicked are doomed to the same fate after death and are subject to an eternity of an unconscious, memory-less spirit. Job 14:21 affirms this belief.

Why are the righteous and wicked equal at death? Why do wicked men prosper in this world while righteous suffer? This is the million-dollar question Job struggles with throughout his treatise. The Psalmists also deal with this dilemma.38 But never do they opine an afterlife in which there’s a paradise for the righteous and hell for the wicked.

In fact, whenever the Psalmist dooms the wicked to “sheol,” it is clearly a reference to their speedy, untimely death – and is not a reference to a place called hell. This is clear from the context of these statements.39

According to the Garden of Eden narrative in Genesis 3, had Adam not eaten from the Tree of Wisdom mankind would have been immortal. Death was a “curse” resulting from that sin. It was not intended to happen all along as some sort of “time of judgment” for people’s actions during their life on Earth.40 This explains why nowhere in Tanakh does it talk of the incentives of paradise or the deterrence of hell. It simply had no belief in such an afterlife. Instead, Tanakh repeatedly emphasizes the physical rewards and punishments associated with obedience to the Torah law.41

Man’s abode is on Earth, and after death the spirit descends into Sheol where it forever resides never to be resurrected. This is the opinion of Job in 7:9-10 of his book, as well as in 14:12. Ps. 88:6 implies a divine disregard to the dead, as does Isaiah 38:18.. Daniel 12:2 is the only reference to a resurrection after death (for some people), and it has been dated by historians to be the latest book of Tanakh, written in the Hellenistic era.42

Sheol was believed to be a pit-like vault under the ground we stand on.43 Korach and his sons were swallowed alive into this pit.44 This pit was well-known to the ancient Near East which shared the belief in this unlively underworld chamber. To the Babylonians it was called Irkalla and it was ruled by the deity Ereshkigal.45 In some Babylonian myths, Irkalla is guarded by seven walls and the funeral rites of the living for the deceased allows for the safe passage through these seven barriers.

Despite the fate for all to Sheol upon death, the biblical account talks of several people who were spared from Sheol, and, assumedly, were deified. Concerning Enoch it says “Enoch walked with God; then he was no more, for God took him.

“46 This implies that Enoch went above to God’s realm, instead of descending below to Sheol. Similarly, Elijah the Prophet is said to have been taken up by a whirlwind from heaven on the day of his passing from Earth.47 The Psalmist also prays that he too be taken up to God for eternity, rather than be cast down to Sheol.48

By Talmudic times, we have various levels introduced to the Sheol afterlife, with paradise for the righteous and hell for the wicked. This was likely influenced by the dominant Zoroastrian culture of the time which emphasized judgment in an afterlife. Hell was imagined to be either in the sky, above the firmament, or below, in the underworld.49

Yet another opinion is that it is beyond the “Mountains of Darkness.”50 This mountain range was somewhere in Africa and Alexander the Great is said to have consulted the sages about how to pass the mountain range in order to conquer the legendary Amazonian kingdom beyond the mountains.51

Interestingly enough, this legendary mountain range may have already been in popular mythology from the 6th-century BCE, in a Babylonian map called Imago Mundi. It depicts the known world of the ancient Babylonian. It includes the great city of Babylon, surrounding rivals like the Elamites in Susa and Assyrians in Assyria. The great river, the Euphrates, passes through all these regions.

Encompassing the land was the “bitter river” (a reference to the salty ocean) with triangle-shaped regions on the other sides of them (most likely mountains that were seen protruding out of the horizon at the oceans). These regions would have been unreachable and attracted the lure of mystery and imagination. Each mountain range had its own unique characteristic. One of these mountains is described (in the cuneiform text on the reverse side of this clay map) as being a “great wall” which blocks out all the Sunlight from entering it. The parallels to the impassable Mountains of Darkness in Greek and rabbinic literature seem obvious.

A 6th-century BCE Babylonian map of their known world

The Ends of the World

The world, to the ancient Near Eastern of the second and first millennia BCE, was miniature compared to the actual settled world at the time. There were peoples and nations living across each region of all 6 continents at the time. Yet only a select few were known and recorded in the biblical books. These cities, nations, or regions mentioned correspond with the known market routes of the time. It would take the later Roman Empire to build up the highway system for Middle Easterners to know of distant places like China and Western Europe.

Genesis Ch. 10 records the nations of the world, approximately 70 of them. Based on context and other sources, we could decipher the identity of practically each of these listed nations.

Of all the nations listed there and elsewhere in the biblical books, the farthest out West were the island nations of Greece. There is no mention of the Italian peninsula or beyond. The most Northern nation mentioned is Ripat and Magog, corresponding roughly to the Caucasus region or perhaps as far North as Southern Ukraine. The Easternmost nation mentioned is Iran, with a possibility that India might also be referenced.52 The Southernmost regions were that of Arabia and Kush in the African continent. The rest of the world’s regions – Northern Europe, Western Europe, Central Asia, East Asia, Central, Western, and Southern Africa, the Americas – were all not known to the ancient Israelite. The world was simply a much smaller place.

The Heavenly Heavens

At this point the rain has stopped and Utz finished explaining the intricate diagram carved into the soft sand. We exited the shelter of the grove and stood under the naked sky. He lifted his hands up to the heavens and thanked God for the surreal encounter he had with a man from the future. But I wasn’t ready to depart just yet.

“Who are you praying to?” I asked Utz. “To the God of Israel, who dwells on high, who rides the skies, and who’s Face of Glory cannot be perceived by us mortals on Earth.” I paused in confusion. I recognized all these phrases from Tanakh, but have never put them all together in one sentence. Could God actually be in the literal skies, according to Tanakh? Are there actually two heavens – the physical and the spiritual – as I was raised to believe, or does heaven just mean, well, heaven?

To solve this question, we trekked to the nearby city of Shechem and consulted the local priests who served as teachers for the masses. They had a collection of handwritten scrolls comprising the books of Tanakh, which they gracefully let us borrow.

Who built his chambers in heaven

And founded his vault on the Earth,

Who summons the waters of the sea

And pours them over the land—

Whose name is YHWH.

-

Amos 9:6

“The heavens are the heavens for YHWH, and the Earth was given to mankind.” -

Psalm 115:16.

God’s throne is described repeatedly as being in the sky/heaven (shamayim in Heb.)53 and is covered over by the clouds so that we cannot see Him.54 He rides the heavens,55 or the “ancient” heaven of heavens.56 From on top he presides over mankind and sees the world from a distance just as a man “sees a grasshopper.”57 He will “go down” in order to inspect various cities and to achieve various Earthly tasks.58 Elijah the Prophet ascends to God in a whirlwind to the sky,59 and in Jacob’s dream the angels are entering and exiting Earth using a ladder that peaks in heavens.60 The divine sacrificial fire is also described as descending from above.61 Similarly, the fiery hail used to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah were sent “from God from the sky.”62 Finally, the Nephilim – literally, “fallen ones” – are the hybrid human-angelic species of people described in Genesis 6:4. Their name “the fallen ones” implies a descent from heaven above, the abode of the angels surrounding god.

This depiction of God being in heaven is further illustrated in the surrounding cultures whom the Israelites neighbored and were influenced by. The Myth of Etana, an ancient babylonian tale, describes an eagle taking the king all the way through the heavens to the realm of the gods. The closest Jewish parallel to this is the prophet Ezekiel who beholds God’s glory in a vision after “the heavens are opened” for him.63

The Egyptians painted vivid images of their chief Sun-deity, Ra, traveling along the sky by means of boat along the upper ocean.

Indeed this may be the explanation for Psalm 29 which states:

The voice of the Lord is over the waters;

the God of glory thunders,

the Lord, over the mighty waters…

The Lord sat at the floodwaters;64

the Lord sits (enthroned), king forever.

Although not part of the official canonized books of Tanakh, the second-temple era book of Enoch sheds light on the Israelite conception of heaven and Earth. In it, Enoch travels to the ends of the Earth where he peeks into one of the windows of heaven and sees the secret divine chamber of the skies.

“I went to the extreme ends of the Earth and saw there huge beasts, each different from the other and different birds (also) differing from one another in appearance, beauty, and voice. And to the east of those beasts, I saw the ultimate ends of the Earth which rests on the heaven. And the gates of heaven were open, and I saw how the stars of heaven come out…”

- I Enoch 33:1-2.

Every indication is that when it says God is in the “sky/heavens” it literally means sky/heavens. This are several indications for this:

- The Hebrew “shamayim” (sky/heavens) always means a literal heaven. There is no clue anywhere in Tanakh that there is another heaven out there in some spiritual dimension.

- The extra-biblical sources cited earlier all clearly believed in a literal place in heaven for the deities: The Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, and like we see in the book of Enoch the Israelites as well. It stands to reason that the biblical authors – like everyone else at the time – shared that same belief.

- The verbs used to describe God’s movements and actions, cited earlier, all have connotations of a literal sky – “went down,” “in a raincloud,” “went up in a whirlwind,” “hail and fire from God from the sky,” seeing mankind from a distance “like grasshoppers,” etc.

Despite all this, there are several places in Tanakh where God is described in somewhat omnipresent terms. For example,

If a man enters a hiding place, do I not see him? —says the Lord. For I fill both heaven and Earth —declares the Lord.

- Jeremiah 23:24

Other passages also imply a form of divine omnipresence.65 To settle this discrepancy – is God in the sky or everywhere – three possibilities can be proposed:

- It is possible that the multiple voices among the biblical authors may have varying opinions on the matter of omnipresence. There are other examples of biblical contradictions that can only be explained as being diverging voices in ancient Israel.

- God is in heaven, but this dominion and glory are found everywhere. Much like a king whose palace is one place, but he has the ability to travel around anywhere in the empire he controls. This seems like the most likely explanation based on the verses. Here’s one example:

The Lord has established His throne in heaven,

and His sovereign rule is over all.

- Ps. 103:19

- God is (spiritually) omnipresent but His glorious manifestation – a physical expression of His – is specifically in heaven.

While perhaps theologically complicated and thought-provoking, this recognition of a God in the literal sky – according to the biblical authors – makes sense of all the verses. Attempts to reinterpret their words serve the authors injustice. Their original intent seems obvious to the honest reader. For me, it took Utz to come to this realization. It’s now time for me to fly back to reality – I only wish Utz could fly with me in an airplane above the firmament so he can get a view of the mysterious world he could only imagine.

Footnotes

-

Pesachim 94b. Genesis Rabbah 6:8. ↩

-

Generally a reference to the Greek astronomers in talmudic literature. ↩

-

In reality, the reason for this is because the oceans and lakes are so large that they contain the heat from the day within themselves longer than it takes for the atmosphere to cool down. ↩

-

There’s an irony in the claim of many Orthodox Jews that the sages were infallible, in the fact that Rebbi himself admits that the sages were erroneous. Turns out, Rebbi himself was fallible and mistaken. ↩

-

In fact, Rabeinu Tam (12th-century French Rabbi) is quoted as having used this as a proof that the Sages of Israel were in fact correct about their understanding of the Sun’s rotation (Shitah Mekubetzes to Kesuvos 13b). ↩

-

Jerusalem Talmud, Avoda Zara 3:1. ↩

-

This might help explain the phrase there that the ocean was like a “bowl/plate.” Radak on Isa. 42:5 implies exactly this regarding the shape of the Earth which he describes simultaneously as a “ball” and as a “coin.” Similarly, Ramban on Num. 7:3 also implies that the Earth “ball” is a round-shape by circumference only (like the silver basin). ↩

-

Midrash Bamidbar Rabbah 13:17. Tosafot avoda zara 41a. See also Zohar vaYikra 10a. Although the authorship of Zohar is traditionally ascribed to 2nd-century Shimon bar Yochai, critical (and traditional) scholarship has demonstrated that at least large parts of it – if not most – were written up during the 10th-13th centuries. The Zohar goes on to claim, without evidence (and evidence to the contrary), that this was a deep held secret among the Jewish sages for generations. It continues to describe a seven-layer sphere (like an onion) with Israel and Jerusalem at the highest of the spheres. Paradise and hell are positioned between these spheres. Descriptions are given about two-faced species on the other side of this globe. There’s also a fantastical story told there of a sage who got lost at sea, but finds a subterranean tunnel that takes him to the other side of the globe where he encounters a race of midgets. The nature of this Zohar discussion is either spiritual or primitive and fantastical. Either way, it does not hold up to scientific scrutiny. ↩

-

Talmud, Kiddushin 69a, Sanhedrin 87a; Zevachim 54b, Midrash Sifri, Ekev 1. Also see Shabbat 65b and its commentary by Rashi and Tosafot. ↩

-

Ez. 5:5 and 38:12. See Derech Eretz Zuta 9:4. Midrash Tanchuma Kedoshim 10. ↩

-

Most notably the Dendera temple. ↩

-

Papyrus mythologique de Tanytamon, Egyptien 172. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des manuscrits (color and luminosity modified on gimp) : https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8304598h ↩

-

Tablet 4, lines 137-140. ↩

-

We know of this event from two sources : Strabo (Geographica, VII-3-8)1 who was paraphrasing Ptolemy Sôter description of the encounter between Alexander and Celts (i.e. the populations met by Greek in southern France and northern Italy) and Arrian2 (Alexander Anabasis; I-4) probably taking from the same source. ↩

-

Chagigah 12b. ↩

-

Bereshit Rabbah 4:5. ↩

-

Bereshit Rabbah 4:5. According to this opinion, the Sun, Moon, and stars appear to rotate under the firmament rather than being pinned in it. This seems to be the viewpoint of many rabbinic rabbis. ↩

-

Jerusalem Talmud, Berachot 2c. According to yet another opinion (Pesachim 94b) it is 1000 parsas deep (appr. 2660 miles). ↩

-

Tamid 32a. ↩

-

And perhaps as high as the realm of the gods. More on this realm later. ↩

-

Cf. Pesachim 94b. ↩

-

Genesis 7:11, Genesis 8:2, 2 Kings 7:2, 2 Kings 7:19, Isaiah 24:18, Malachi 3:10 ↩

-

Job 37:11, Ps. 135:7, 1 Kings 18:44-45. ↩

-

Alternatively, they may have seen the clouds as being a visual barrier to block the “heavenly windows” from being seen through by humans as they open up to pour down rain. The cloud is often seen as a visual barrier for humans from seeing the divine. See Exodus 19:9-13, 1 Kings 8:10-11, Exodus 40:34-35. ↩

-

J. Talmud Rosh Hashana 2:4. ↩

-

Pesachim 94b. ↩

-

Chagigah 12b and Job 38:22. ↩

-

V. 32. ↩

-

See Job 26:7 and Isa. 14:13. ↩

-

Quoted in Rashi’s commentary to Gen. 1:6. ↩

-

Chagigah 12b. ↩

-

Chagigah 11b. ↩

-

Chagigah 12b. ↩

-

See here https://jewishbelief.com/the-evolution-of-moshiach/ for more on the subject of the resurrection in biblical sources. ↩

-

Genesis 25:8, Genesis 35:29, Genesis 25:17, Genesis 49:33, Numbers 20:24, Numbers 27:23, Deuteronomy 32:50. This cannot be a mere reference to being buried in the lot of their ancestors, since some of them were not buried alongside their ancestors: see Genesis 25:9, Numbers 20:22-29, and Deuteronomy 34:6. ↩

-

Genesis 25:9. ↩

-

Psalm 6:6, 30:9, 115:17. ↩

-

Ps. 37, 73, 92 and more. ↩

-

Example: Ps. 9:17. ↩

-

The Garden of Eden was a physical place on Earth – not to be confused with the rabbinic perception of a spiritual paradise in heaven. ↩

-

Example: Lev. 26 and Deut. 28 & 30. ↩

-

See here https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-lead-up-to-chanukah-in-the-book-of-daniel ↩

-

Isaiah 14:15, Psalms 88:3-6, and Proverbs 7:27 among others. ↩

-

Numbers 16:30. ↩

-

See here for more on this https://www.worldhistory.org/article/701/ancient-mesopotamian-beliefs-in-the-afterlife/ ↩

-

Genesis 5:24. ↩

-

II Kings 2:11. ↩

-

Ps. 49:16. ↩

-

Tamid 32b and Bava Batra 74a. ↩

-

Tamid 32b. ↩

-

Tamid 32b. ↩

-

I Kings 8:30 , Ps. 11:4, Ps. 103:19, Ps. 14:2, Deut. 26:15 and more. ↩

-

Job. 22:14, 26:8-9. ↩

-

Deut. 33:26. Also see Isa. 19:1 where a cloud is used for this heavenly transportation. Also see Psalm 18:9-10, Psalm 68:4, Psalm 104:3. See Genesis 3:8 which implies God travelling in a wind. ↩

-

Ps. 68:34. ↩

-

Isa. 44:22. ↩

-

The Sumerian civilization is visited by God’s descent in Genesis 11:5 (see also 11:7). The city of Sodom is later visited in Genesis 18:21 also by God descending. ↩

-

II Kings 2:11. ↩

-

Genesis 28:12. ↩

-

I Kings 18:38. Also see II Chronicles 7:1-3 where the divine fire and glory descend onto Solomon’s inauguration sacrifices. Also see Ex. 19:18 in the context of the Mt. Sinai revelation. ↩

-

Genesis 19:24. ↩

-

Ez. 1:1. ↩

-

Cf. Gen. 7:11. ↩

-

Ps. 139:7-8, and perhaps I Kings 8:27 and Isa. 66:1. ↩